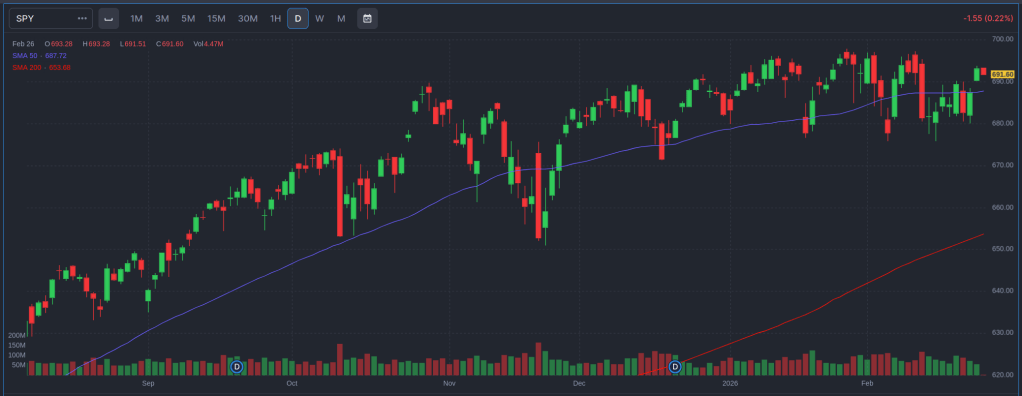

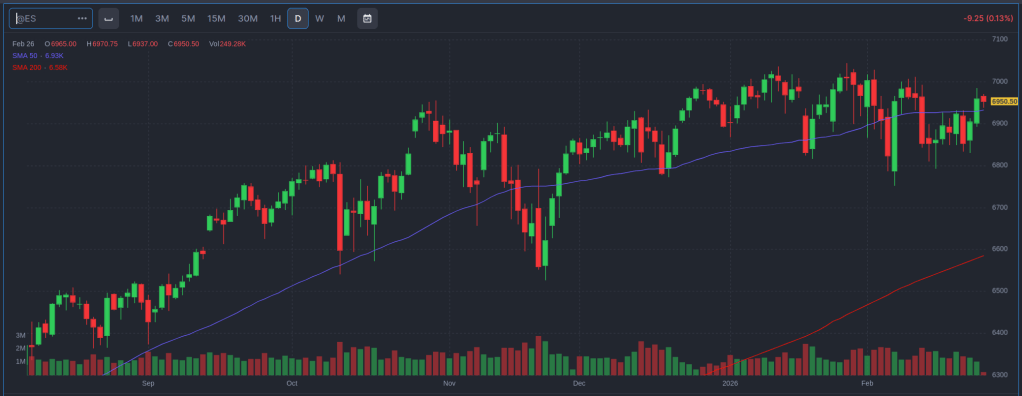

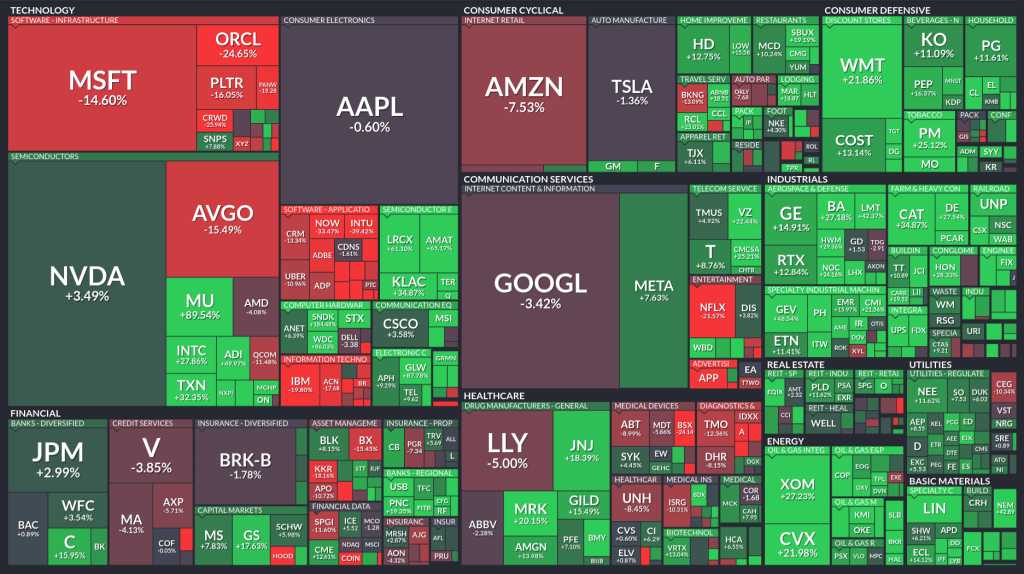

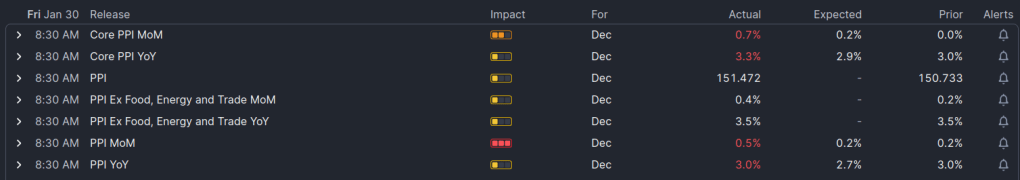

Taken about 8:45 AM EST in the pre-market. In short, this is the PPI coming out hot. 2.9% annual inflation versus and expected 2.6%. For the market this is as bad as, if not worse than, the CPI coming in hot. If the CPI comes in above estimates, that just means rates might rise. But if the PPI comes in hot, and the CPI doesn’t, it means margins get squeezed. It means that for a $100 of revenue, it means less profit. If both CPI and PPI were going up, that’s not good, but businesses are able to hold their margins. As happened earlier in the inflation burst, CPI went up faster than PPI in some cases, and margins expanded.

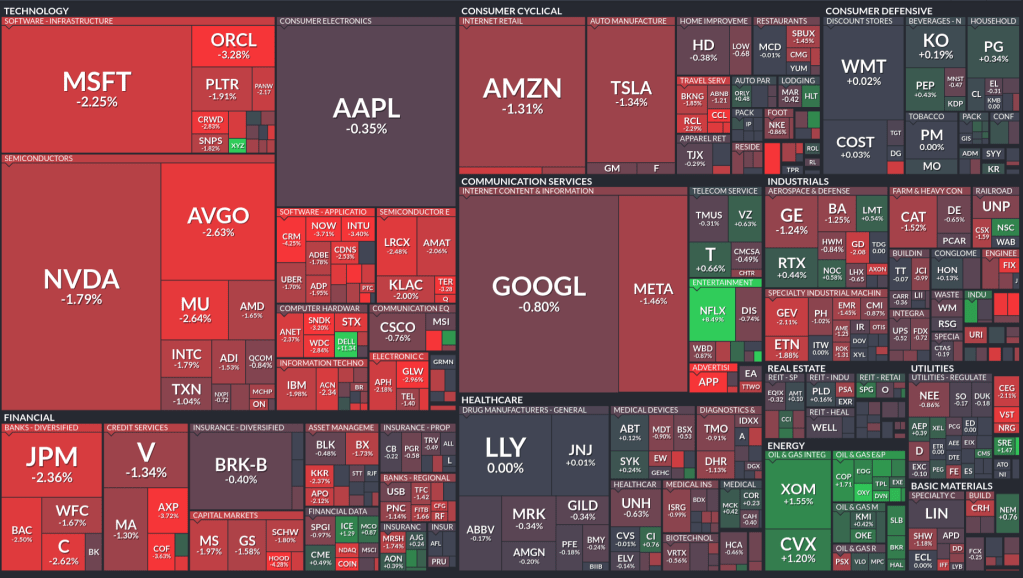

That explains some of the impact. The other part of it is the idea that AI isn’t playing out the way people hoped it would. We are seeing a concerted push by companies to adopt AI and (despite the protestations of $XYZ – Block), we have yet to see significant changes in productivity. There may be reasons for this that have nothing to do with AI. First and foremost, it’s a new technology. The “recipe” for mixing it into an organization to boost productivity and reduce costs may need to evolve. With a lot of churn, it’s hard to know if chat bots, RAG (retrieval assisted generation), or some yet undiscovered pattern will produce the best outcome. One that doesn’t give away free stuff from vending machines or cite non-existent cases in court filings. (So, how much do you want to trust an LLM to correctly categorize a major business expense that could cost you in interest an penalties?) But until we do it looks like NVidia may be the only winner as they sell more GPUs to companies that may not have the electrical grid power to turn them on?

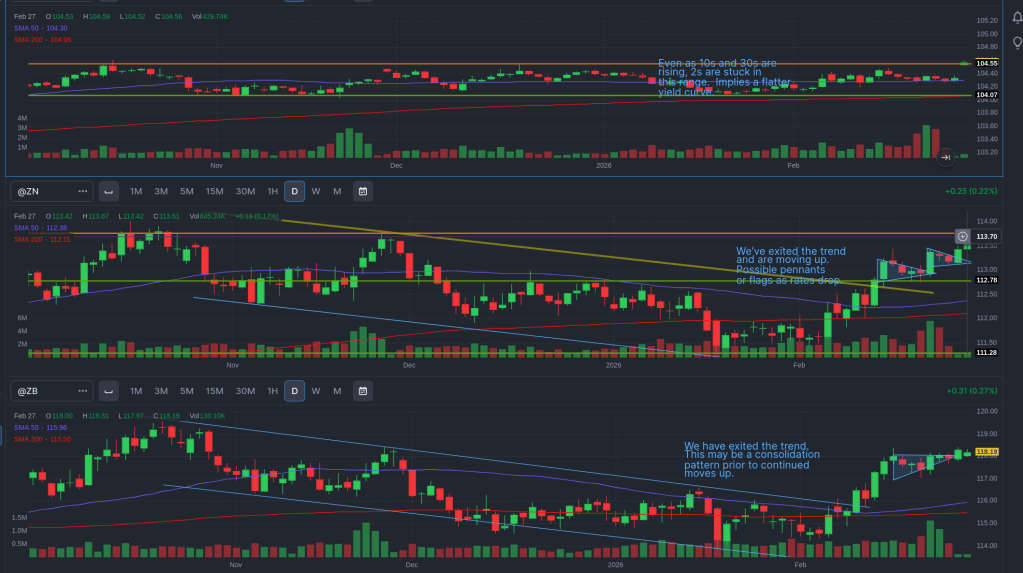

But let’s get back to macro. Long rates are dropping, but the 2-year is kind of holding in a range. These are bond price futures, meaning when they go down, interest rates go up. (The price of a bond is the inverse of the rate). The bottom two are 10 and 30 year bonds, respectively. Businesses are generally sensitive to the 10 year rate. Prices were falling on the 10 and 30 up to February, ,while the 2 year stayed in its trading range. (I kind of compressed the 2 year graph to give a better sense of how little movement there was in the 2-year, given a similar $3 range in the 10 year). The fact that long bond prices were going down, while shorter term maturities were stuck, meant that long rates were coming down while short rates were holding. (The shorter you go the closer you track the Fed Funds rate).

A normal yield curve has the lowest rates for the shortest maturity debt. Everything beyond that carries more risk. These risks may be interest rate risks (the interest rate falls and so the price of your bond falls), or re-investment risk (the rates go down and you can’t re-invest at the same rate). There’s almost no risk at 30 days to 90 days. At thirty years, there’s almost a certainty things will be different and you might be underwater in your bonds or unable to secure a similar rate when the principal redeemed. The price of the bond is a negotiation between buyers and sellers about future interest rate risks.

When the price of long bonds start going up, it means that people are betting future rates are going to be lower. This is because they expect lower demand for capital in the future – likely because the economy is slowing. A rate inversion, when the rate on the long bond falls below the short rates, is a sign investors expect the economy to be in recession so rates will be reduced to stimulate the economy. That’s why we get yield inversions, and why they tend to be at the start of, or just in front of a recession. Also, in most cases, the short term rates go up because the Fed has been slowing the economy. This last inversion period was both large in scope and did not result in a recession, so far1. (And there won’t be as much borrowing to invest in new businesses). What you want to see is the entire yield curve (the interest rates at various maturities) move down together. Lower rates plus strong future expectations.

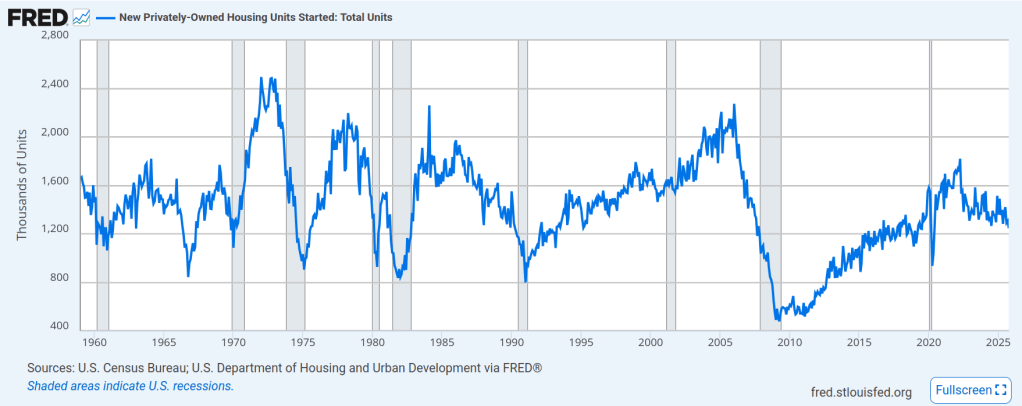

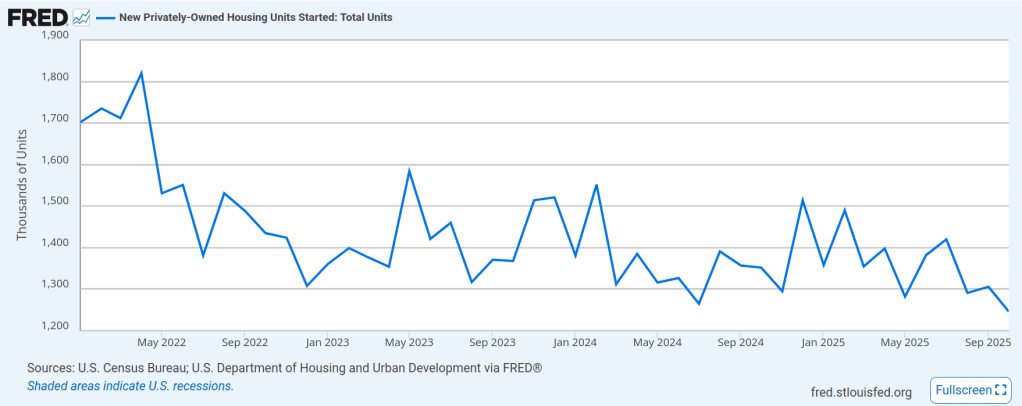

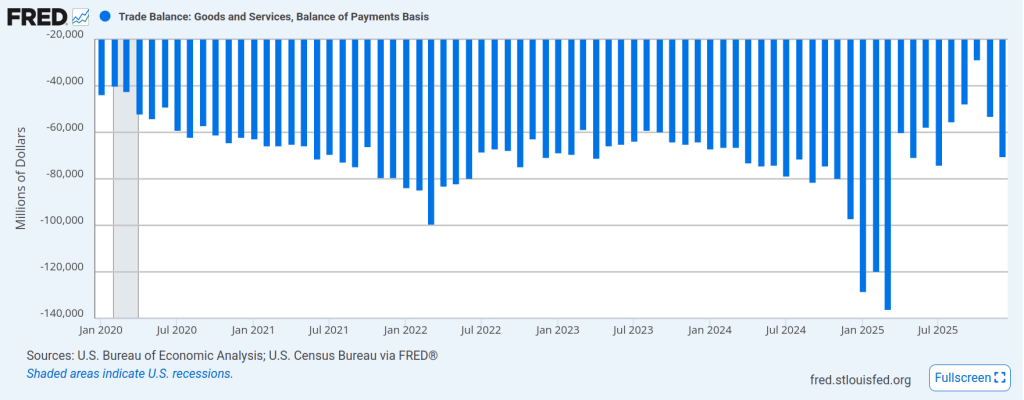

Which brings me to this graph, the balance of payments (trade deficit). If you eye-ball a line across the graph, between -60,000 and -80,000, you probably have close to the average trade deficit. Then you have “Liberation Day” in April and a huge spike. What’s that about? Those are businesses bringing in inventory prior to the tariffs taking effect. That inventory was spent down in the next few months, as businesses imported less because their inputs were sitting in warehouses. At some point they are going to have to bring in more product, and that’s why I think we’ll be back to roughly the same (maybe a hair smaller) trade deficit. We’ll have to see how it plays out, but the last reading was in line with the historical average.

That suggests that businesses are continuing to import final goods and inputs for their manufacturing at nearly the same rate as before the tariffs. Some businesses elected to eat the tariffs (note it is businesses that pay tariffs, not governments) rather than pass those costs onto consumers. They were assuming the tariffs would get rolled back and it’s better not to piss off your customers. They might even get refunds. But given the number of businesses that sold the refund rights to Lutnick’s kids at 20 cents on the dollar (yes the same one working for the president as the secretary of commerce), I don’t think they held out high hopes. We’ll have the lovely spectacle of the commerce secretary’s kids suing the federal government for refunds of illegal tariffs imposed by the administration, which they scooped up at bargain basement prices. Ain’t corruption grand?

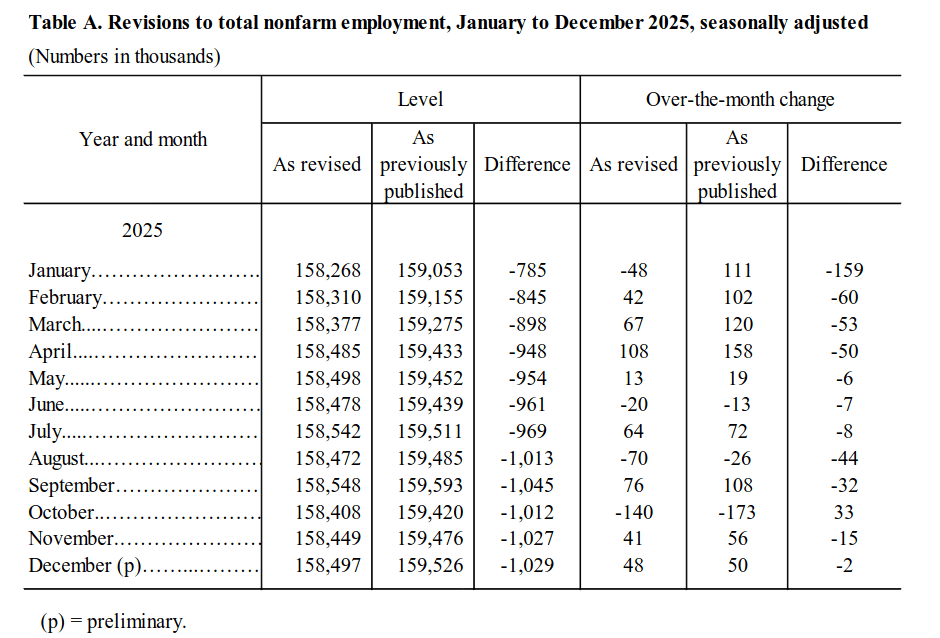

If businesses are importing as much, and they are paying higher prices, and they have spent down their inventory, we might FINALLY start seeing the consumer level inflation impacts of tariffs. But we’ll first see it at the business level. Businesses have eaten the tariffs, for now, but will either suffer lower margin or start passing on those costs. That means businesses will start cutting costs to deal with tariffs and the easiest way to cut costs is to reduce head-count. When people no-work they no-spend. Block’s hope is the reduction in headcount (maybe over-hiring a few years ago), will result in better margins as costs fall, even if revenue falls. But, like I said earlier, there is no clear indication we’ve figured out how to incorporate AI into businesses or operate an AI provider profitably. It’s all subsidized by giant pools of investor money.

If you expect a softer economy (not radically expecting recession tomorrow), you want to hedge your risk (equity) exposure by buying bonds. Foreign companies have become a lot more wary of buying bonds, except there is no other currency with the depth of the dollar. And therefore US debt is still attractive. (TINA – there is no alternative right now). If short rates hold up because inflation actually starts making its way into the consumer market (not in one quick burst but trickling in as business after business has to raise prices), and the Federal Reserve can’t cut without resuming inflation, you should expect the economy to slow. By how much? I don’t know, but I would not expect long rates to stay where they are. I expect them to come down, or there is an increase that the Federal Reserve would need to step in by shoving liquidity into the system.

The two year has been betting the interest rates will stay about the same. Until February, the long rates were making similar bets (or maybe a little AI optimistic combined with nervousness about the Fed forced to cut rates combined with dollar de-risking). They were holding or going up slightly. Now they’re falling, compressing the yield curve. At the same time business costs may be going up. With a Fed that can’t immediately inject liquidity until the economy gets a lot worse. What a lovely little shit-show we’ve built.

This is not investing or investment advice to you, or anyone. It’s is provided for your entertainment purposes only. And if you are investing, contact a professional before making any decisions. Buying and selling stocks, futures, or any investment is a risky activity and can cause you to lose money, including the principal which you invest.

- It may be the ONE TIME that the Fed slowed the economy but didn’t throw it into recession. The so-called soft-landing. Something I did not think could be done and therefore missed out on some returns (albeit at a higher risk). ↩︎