This week is a lighter week.

- Monday – Markets are closed

- Wednesday – Housing starts and FOMC minutes

- Friday – GDP

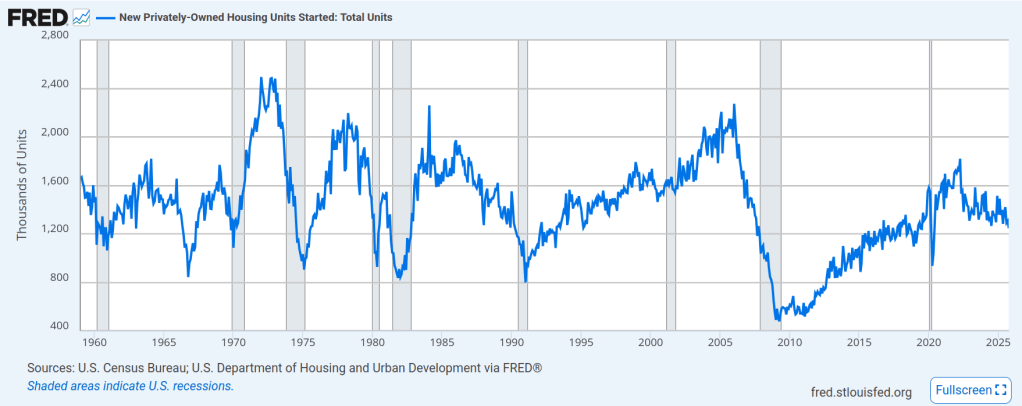

Housing starts I don’t think are as critical as they once were. It used to be that sales of houses were tied to a lot of other economic activity from buying new furniture to updates to existing homes. It used to be more a headline number and market mover.

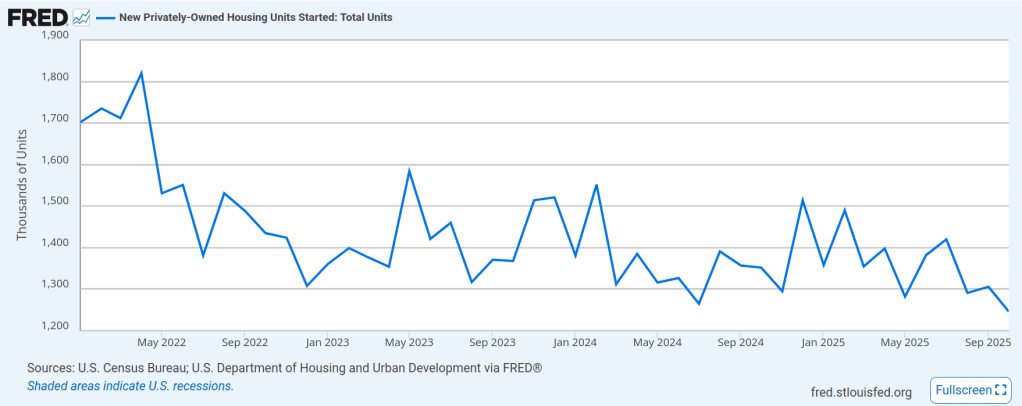

Here we see the last couple years of starts, compared to the historical numbers for housing starts. Although housing remains unaffordable for many, we don’t see a huge increase in starts over the last three years. From the chart above, we can see a jump shortly after the COVID lockdowns, but nowhere near enough of a bump to deal with the lack of housing created after 2008. And if you have to ultra-stretch your budget for a house, that doesn’t leave a lot for new furniture or trips to Home Depot.

The FOMC minutes, however, will be interesting to see. We’ll get a view of how hawkish or dovish the over-all committee is. And remember, even if Trump installs a rate-cut happy lunatic as Fed chair, that lunatic doesn’t set policy. It’s voted on by the full committee. Which is why Trump is testing his ability to fire other Fed members. In the presence of tax cuts and proposed spending increases, a Fed that cuts rates will be adding stimulus on top of stimulus when the employment rate is in the range of full employment. Which would attack the debt level by devaluing the dollars in which the debt had been issued. But then interest rates (should) climb, or the dollar (should) fall to offset the devaluation of the dollar. When the dollar falls, oil and other commodities climb in price, pushing more inflation. And there is no guarantee that the increase in wages would outpace inflation. We would almost certainly all be worse off.

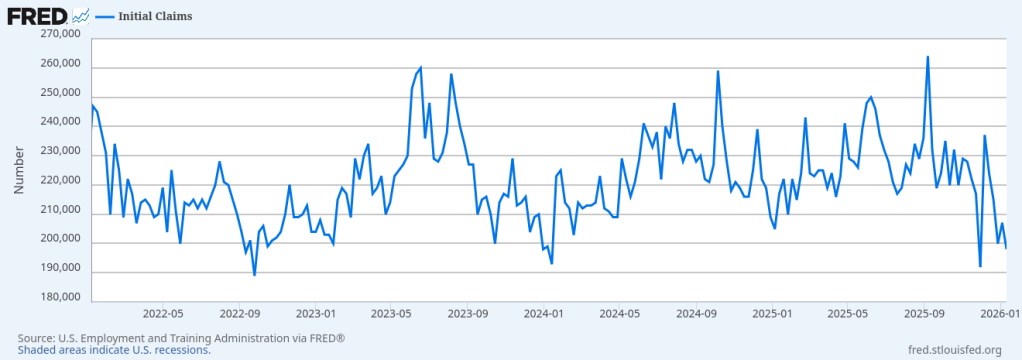

A quick note for folks that think 0% unemployment is full employment, that’s not how it works. Inflation has a statistical relationship with unemployment known as the Philips curve. Below a certain level, like 7% unemployment, a decrease of 1 percentage point of employment has no impact on inflation. At lower levels of unemployment, a 1 percentage point decrease in unemployment drives higher inflation. Why? Because when the labor market gets tighter (and everyone is immediately swept up into a new job), companies wind up bidding up wages to attract workers.

Those workers have more money for cars, food, vacations, and so on, and that drives inflation from the demand side. Also, as wages get bid up, more workers come off the sidelines into the workforce. These range from moms who no longer see it economical to stay at home, or retired people seeing opportunities, or people who left the job market to write a cook-book, etc. You can get a month to month increase in unemployment as these people come back into the workforce, while having a very tight labor market. As we pushed down toward 3% unemployment post-COVID, that contributed to an increase in inflation. It was great because everyone’s salary was jumping, but few people feel it outpaced the impact from inflation.